I loved popular science magazines as a kid in the 80s. Omni, Popular Mechanics, the eponymous Popular Science. I also read the occasional comic book, though they never seemed to give the same bang for the buck; most comic books at the time felt like watching the middle 5 minutes of a soap opera episode.

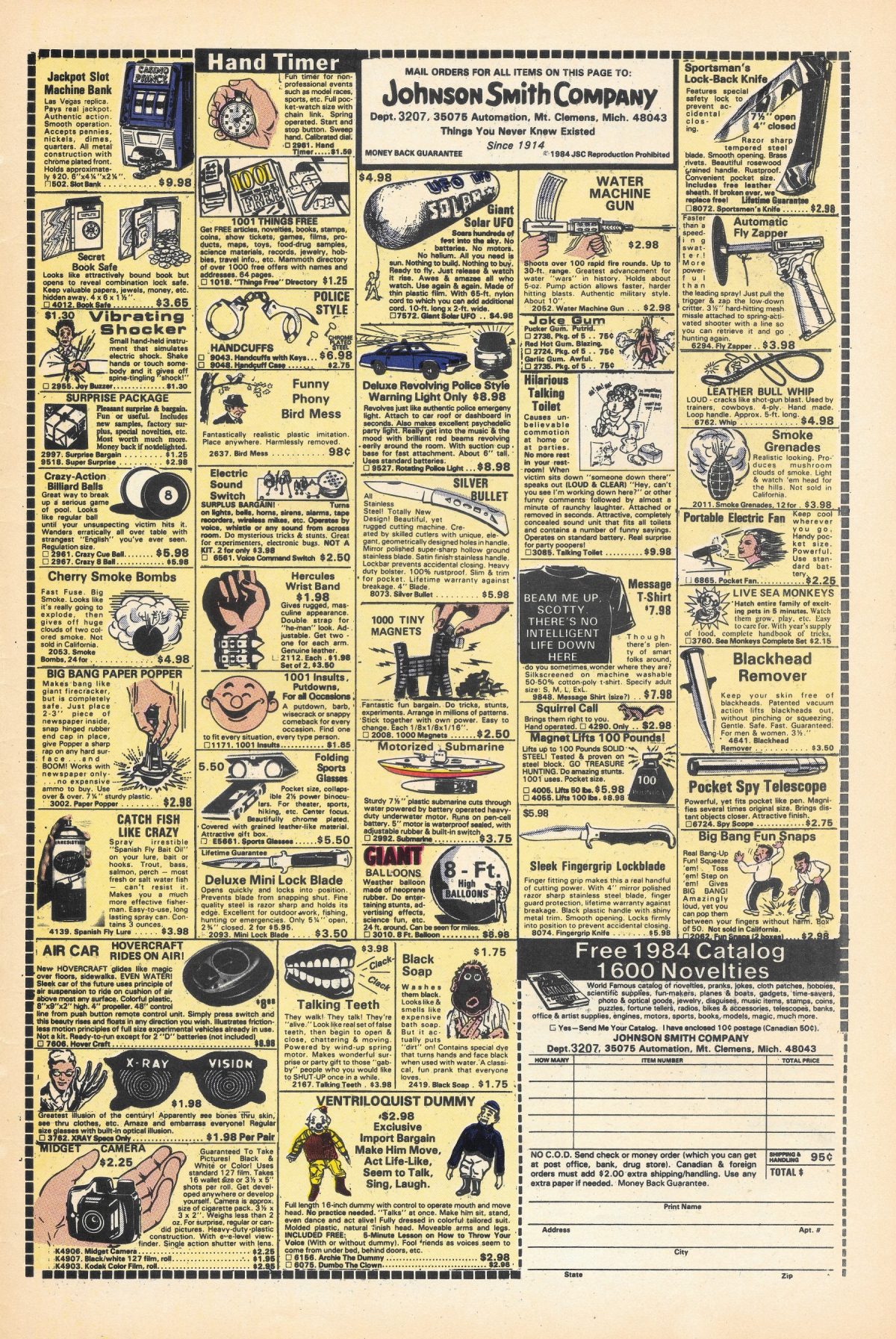

Whenever I could get access to one, I read it cover-to-cover. Well, I probably skipped over the front bits with their opinions and letters, but I definitely spent time on everything in the back, including the ads. The science-magazine ads had a delightful mix of very-specific technical tools I wanted but didn’t understand or couldn’t afford – oscilloscopes, glassware, the occasional computer – but also bizarre ads for dubious contraptions like electric-shock pads to build muscle mass. (That one had a photo of arm wrestling with the huge caption “RUSSIA WINS?” because 80s cold-war movies.) The comic books dispensed with anything scientific or practical and focused on the dubious contraptions, with full-page spreads of “novelty” catalogs. Joy buzzers. Switch blades. Chattering teeth. Mini binoculars and spy cameras. And most intriguing of all: x-ray glasses.

The blurb under “x-ray glasses” always contained the keyword “illusion” to take the sting off, but it was surrounded by enticing phrases like “see bones through skin” and “see through clothes”. As an adult, I can look at that ad and easily spot the real message: this thing provides the illusion of seeing the bones in your hand, if you squint and aren’t familiar with what the bones of your hand should actually look like. If you look at someone from a bit of a distance, their clothes seem to take on a ghostly edge as though you could see through them to what’s behind the person. It’s a bit of a laugh for 5 minutes, and then you put it away.

Oh, but the implications to a kid! Especially a kid who just read through 5 minutes of a GI Joe or X-Men soap opera episode where either technology or “science” gives people powers. What if it really means you can see the bones in your hand, even if it’s using an “illusion” to show them to you? What if the “illusion” of seeing through clothes is of the person underneath, which is as good as the real thing? After all, the joy buzzer does something, and the switch blade is an actual knife, and even the chattering teeth do what they say in the big print.

What if it really works?

And if there was any barrier put up by skepticism or critical thinking, that one question was enough for my childhood optimism to swarm right over. And even if someone else tells me “it says it’s just an illusion”, then I have the perfect counter. I know it’s an illusion, but what if it really works? Bam, if I hold onto that cognitive dissonance, then it’s worth the purchase.

Which works in reverse, too. If I buy the glasses and try them on only to find that it’s an illusion that doesn’t show me bones or bodies or the insides of anything, really… “it didn’t work”. “It said it was just an illusion.” “Oh.” But does that stop the next person? Of course not. Because to them, what if it works? And that’s enough to keep people buying.

All that said, even though I understand the draw, I’d still be shocked if a doctor pulled out a pair of x-ray glasses to diagnose a pain in my arm. “Let’s see if there are any broken bones.” It wouldn’t just be a reason to doubt their diagnosis, it would be enough to doubt their competence.

This isn’t about generative AI specifically, but that’s what brought it to mind. I get sincerely baffled when someone leaps from “it’s just a language generator, but the ad said it could do this” to “I saw a demo that looked kinda like this if you squint” to “I’m going to base a critical decision on this.” “But it doesn’t actually do that,” I say, but they have the perfect cognitive-dissonance counter. “I know it’s an illusion, but what if it works?” And I have no recourse but to wait for the glasses to arrive, to watch them put the glasses on, and then watch them take the glasses off 5 minutes later. I want to be kind. “OK, how would you like to handle that critical decision now?”

It seems like there’s an endless supply of x-ray glasses out there. Crypto. Ride sharing. ”Full Self-Driving”. Or a political candidate. Or a stainless-steel truck. Or a VR headset. Or “we’re going to Mars.” I can point straight at the part of the ad that calls out the illusion. And do it over again. And again.

But what if it works this time?